● Brendan O’Neill, in a column in The Sun, draws attention to what he calls the “Stasi” student unions. Mr O’Neill says the joke isn’t funny any more. It never was, for those on the inside. E.g. the editor of Oxford student magazine No Offence, who was threatened with police action and feared he might be arrested.

A 2016 survey suggested that more than half of university students think it is correct to ban from campus anyone who “could be found intimidating”. By means of relentless propaganda over past decades, the il-liberal elite have managed to shift sensitivities, so that now anything deviating from radical egalitarianism may be labelled offensive or intimidating. A whole range of topics in politics, sociology and psychology have effectively become taboo.

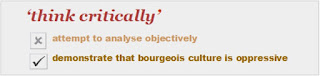

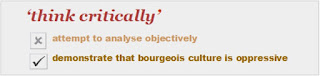

Relatively few people are interested in knowledge and truth for their own sake. Learning to apply an ideology, on the other hand, seems to have greater popular appeal (judging by the history of religion). By massively expanding the student population, the priorities of campus have been shifted away from objectivity and neutrality, towards morality and politics. That may conceivably be good in some ways, but for the quality of debate and research it is disastrous.

● Either my standards are dropping, or BBC drama really is getting better. The Beeb have already demonstrated they can adapt classics in a way that gives priority to art and entertainment over sociology lectures. They have now shown the same for original drama. Six-part series Requiem does an excellent job at keeping high-pitched atmosphere and visuals in balance with strong narrative and characterisation. The supernatural provides a fruitful theme in fiction, but many are put off by the level of grimness which usually accompanies it these days. Requiem is gritty but not brutal.

Key talents behind the camera are Australian writer Kris Mrksa and British director Mahalia Belo.

09 February 2018

02 February 2018

Brexit shmexit

The EU is threatening severe restrictions on consumers’ ability to carry out hedging or investing via spread bets and CFDs.

As is often the case, most corporations and wealthy individuals will experience minimal impact since they will be able to find ways round it. It’ll be the little guy that gets nobbled.

The proposed rules are even more draconian than those suggested by the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority. In theory, the measures are to protect people from themselves, but the case illustrates how EU “harmonisation” has become an excuse for unnecessary cross-border paternalism.

As consumers and voters, we are free to question the motives of the bureaucrats behind such interventions. Do we want their paternalism? Should we accept their rationales at face value? Are state employees distinguished by an above-average desire for interventionist power, for its own sake, which only requires an acceptable cover story to be indulged?

Those who wish to express their views on this latest instance of EU meddling can can use this website, and have until Monday to do so.

As is often the case, most corporations and wealthy individuals will experience minimal impact since they will be able to find ways round it. It’ll be the little guy that gets nobbled.

The proposed rules are even more draconian than those suggested by the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority. In theory, the measures are to protect people from themselves, but the case illustrates how EU “harmonisation” has become an excuse for unnecessary cross-border paternalism.

As consumers and voters, we are free to question the motives of the bureaucrats behind such interventions. Do we want their paternalism? Should we accept their rationales at face value? Are state employees distinguished by an above-average desire for interventionist power, for its own sake, which only requires an acceptable cover story to be indulged?

Those who wish to express their views on this latest instance of EU meddling can can use this website, and have until Monday to do so.

26 January 2018

Peer scrutiny

The second of the two open letters denouncing the Empire and Ethics project — signed by scholars from (inter alia) Cambridge, Princeton, Cornell and King’s College London — exhibits even more contempt and vitriol than the first.

It seems unlikely that the principal problem the signatories have with the project is that it departs from approved academic methodology. That doesn’t prevent them trying to criticise it on those grounds. They object that it is not possible to “demarcate ‘empire’ as a fixed and stable subject”. They complain that the project’s core group “does not represent the diverse constituencies of scholars” working in this field.

These criticisms seem weak, and hardly provide justification for public denouncement. History is plagued with problems of definition and demarcation, yet proceeds in spite of them. There is no principle in academia that a research project must be staffed with representatives from varying schools of thought.

At the end of their letter, the scholars demand that Oxford University clarify

It seems the scholars want to make quite sure that the methodologies of the project will meet with the approval of accredited practitioners. Are they (A) merely being helpfully concerned (on behalf of Professor Biggar, and the University of Oxford) that the research should not fail to benefit from the available techniques and insights of modern academic history?

Or are the scholars (B) adopting an exclusionary tactic? Do they suspect (and hope) that “peer scrutiny” would result in a verdict that echoed their own condemnation?

Possibility (B) raises the following interesting speculation. Is academia’s current obsession with accreditation, technique proficiency, peer scrutiny etc. in fact intended — at least in some subjects — to facilitate the exclusion of certain perspectives, i.e. those at variance with the dominant outlook?

It seems unlikely that the principal problem the signatories have with the project is that it departs from approved academic methodology. That doesn’t prevent them trying to criticise it on those grounds. They object that it is not possible to “demarcate ‘empire’ as a fixed and stable subject”. They complain that the project’s core group “does not represent the diverse constituencies of scholars” working in this field.

These criticisms seem weak, and hardly provide justification for public denouncement. History is plagued with problems of definition and demarcation, yet proceeds in spite of them. There is no principle in academia that a research project must be staffed with representatives from varying schools of thought.

At the end of their letter, the scholars demand that Oxford University clarify

the research protocols that will be put in place to ensure that [the project’s] outputs are subject to due peer scrutiny [...]

It seems the scholars want to make quite sure that the methodologies of the project will meet with the approval of accredited practitioners. Are they (A) merely being helpfully concerned (on behalf of Professor Biggar, and the University of Oxford) that the research should not fail to benefit from the available techniques and insights of modern academic history?

Or are the scholars (B) adopting an exclusionary tactic? Do they suspect (and hope) that “peer scrutiny” would result in a verdict that echoed their own condemnation?

Possibility (B) raises the following interesting speculation. Is academia’s current obsession with accreditation, technique proficiency, peer scrutiny etc. in fact intended — at least in some subjects — to facilitate the exclusion of certain perspectives, i.e. those at variance with the dominant outlook?

19 January 2018

You can’t do history if you’re not one of us

Keith Windschuttle, author of The Killing of History:

From a 2005 interview with the Financial Times.

“I got tired of leftwing theories and very tired of leftwing people, quite frankly, and, at the same time, the universities filled up with leftwing people. By the 1980s, to teach humanities you had to be on the leftwing or no one would even consider you.”

The historical establishment and the intellectual elite saw Windschuttle as another manifestation of the conservative ascendancy [in Australian politics]. They closed ranks, suggesting among other things that, because he was not a professional academic, he was not a “proper historian”.

From a 2005 interview with the Financial Times.

12 January 2018

Tutors who know best

The open letters attacking the Ethics and Empire project merit careful study. They are revealing, not just about the state of academic history, but about the purposes of academia, as conceived by the current incumbents.

For example, the Oxford scholars — a group which includes three professors of modern history — say that they teach their students

Here is my advice to undergraduates studying modern history at Oxford. If you want to learn to think seriously and critically, take an interest in the Ethics and Empire research, as well as any other heterodox projects you come across, irrespective of what your tutors may say. Do not commit the same mistake as some members of the history faculty, of writing such projects off a priori.

Of course, in my experience a significant proportion of Oxford students these days are not interested in thinking critically, but merely want to be able to get a good degree and a good reference from their tutors. If you fall into this category, you are unlikely to benefit from considering ideas other than those endorsed by your tutors, and I recommend you stick to those.

In neither case do I recommend repeating unendorsed ideas in your tutorials or exam papers.

For example, the Oxford scholars — a group which includes three professors of modern history — say that they teach their students

to think seriously and critically about [the histories of empire and colonialism]yet go on to assert that

Neither we, nor Oxford’s students in modern history, will be engaging with the Ethics and Empire programme [...]

Here is my advice to undergraduates studying modern history at Oxford. If you want to learn to think seriously and critically, take an interest in the Ethics and Empire research, as well as any other heterodox projects you come across, irrespective of what your tutors may say. Do not commit the same mistake as some members of the history faculty, of writing such projects off a priori.

Of course, in my experience a significant proportion of Oxford students these days are not interested in thinking critically, but merely want to be able to get a good degree and a good reference from their tutors. If you fall into this category, you are unlikely to benefit from considering ideas other than those endorsed by your tutors, and I recommend you stick to those.

In neither case do I recommend repeating unendorsed ideas in your tutorials or exam papers.

05 January 2018

The ‘wrong’ questions

If someone had wanted to expose the less visible biases of academics – which may buttress the more blatant ones of student unions – they could hardly have done better than propose a research project on the British Empire. The topic seems to press some of the most sensitive buttons of the intellectual elite.

The Ethics and Empire project, being run by the University of Oxford’s McDonald Centre and led by theology professor Nigel Biggar, claims to be looking at the issue of empire in a less negative way than is usual. This, apparently, is like a red rag to a bull.

The project has generated open letters of indignation from (so far) two groups of academic historians. The letters are aggressively disapproving, and complain that Oxford should not be supporting this kind of research. The first letter is from scholars within Oxford itself – demonstrating that the place is no stranger to political correctness.

“We write to ...

express our opposition to [...] the agenda pursued in [the] recently announced project entitled “Ethics and Empire”the Oxford scholars say, and go on to hurl a range of hostile epithets including: discredited, bad history, politically naive, swaggering, absurd, caricature, nonsense, useless, polemical, simplistic. The project is said to “ask the wrong questions, using the wrong terms, and for the wrong purposes”.

According to student newspaper Cherwell, the University has responded by confirming its support for the project.

[...] an Oxford spokesperson has now [stated] that the University supports “academic freedom of speech”, and that the history of empire is a “complex topic” that must be considered “from a variety of perspectives”.However, Cherwell seems to be the only source for this alleged support, and the spokesperson is not identified.

They said: “This is a valid, evidence-led academic project and Professor Biggar, who is an internationally-recognised authority on the ethics of empire, is an entirely suitable person to lead it.”

The signatories to the letters clearly do not like the sound of the project. They express both professional and moral reservations. Curiously, they seem to believe it is right to turn those reservations into a collective public attack.

Perhaps the project’s aim is simplistic, but surely no more so than countless other research projects. And perhaps the approach is at odds with orthodoxy, but so what? Neither of these criticisms are grounds for public denouncement, by people who sound as if they are speaking on behalf of an entire profession.

The Oxford open letter attacks the empire project by invoking (among other things) ideals of scholarship, criticalness, and openness. It accuses its target of complacency, and of making simplistic moral assessments. These accusations smack of hypocrisy. The signatories have themselves allowed simple-minded moral assessment to displace objective enquiry. If they were genuinely interested in “open, critical engagement” they would refrain from stirring up trouble against fellow academics. They would avoid themselves sounding complacent and arrogant about the correctness of their orthodoxy. And they would think twice before making inflammatory statements such as:

For many of us, and more importantly for our students, [Professor Biggar’s views] reinforce a pervasive sense that contemporary inequalities in access to and experience at our university are underpinned by a complacent, even celebratory, attitude towards its imperial past.To threaten that the project reinforces unacceptable attitudes towards inequality seems simple-minded. In any case, the possibility that proposed research might strengthen views that are regarded as ethically dubious should not be cause for denouncement. The signatories to the two letters appear to be unaware of this basic principle of academic enquiry. (Genuine enquiry, that is, as distinct from search for data supportive of a preferred viewpoint.)

Consider the following two alternative positions.

A) Enquiry and debate should be respected, even if one disapproves of the viewpoint or approach adopted.

B) It is right to organise protest against research or speech which adopts viewpoints that are regarded by some as offensive.

Which of these two positions are students of the Oxford scholars more likely to internalise, following their open letter? If B, what will this mean for the likely impartiality of social science research when individuals who are now undergraduates become dons? Or, indeed, for free speech at Oxford, which already seems to be compromised?

* * *

Disciplines such as history, in which interpretation is more important than raw data, are prone to ideological capture. Following such capture, they are liable to become intellectual closed shops. Eventually, the only accredited people in such disciplines are unquestioning supporters of orthodoxy, since they are the only ones permitted to pass the relevant ideological tests (though there may always be a few freak exceptions to the rule).

What can be done once that has happened to a faculty or an institution? One course sometimes proposed is for an external agency to attempt to enforce fair access for dissident ideas.

Another possibility is to support projects by outsiders which, while not necessarily conforming to the standards of the orthodoxy – and largely ignored by it – at least let in a bit of fresh air.

Of the two options, the second seems preferable.

15 December 2017

Down the river of hope

Uptrends climb a wall of worry,Are we witnessing the return of classy in the field of television drama? It is tempting to think so.

downtrends slide down a river of hope.

First, there is Amazon’s The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel (creator: Amy Sherman-Palladino), about a Jewish housewife in 1950s New York who turns to stand-up comedy after the failure of her marriage. True, the central premise is preposterous, and Mrs Maisel (magnetic performance by Rachel Brosnahan) seems to come from a different decade than the other characters. Standard TV ideology inevitably makes its appearance: men are jerks, women are nice and sensible, and capable collectively of solving the world’s problems, etcetera. I have not yet encountered any dastardly Republicans, but it’s probably unwise to get complacent.

However, any such minor defects are forgivable because, aside from the top-notch production values, this is the first English-language TV series with genuine pizzazz since the demise of Friends. Marvellous.

Second, on this side of the Atlantic, the BBC has confounded expectations by dramatising a literary work without indulging in the usual level of ideological revisionism. Howard’s End, a 4-part adaptation of E M Forster’s novel directed by Hettie Macdonald, provides a stunning example of small-screen filmmaking as highbrow art: superb on style, but without the poor quality of content that mars so many other visually impressive products. The acting is terrific, and allows for the build-up of complex psychology. It’s thoroughly watchable, even for those who don’t like Forster.

Two sightings of black swans might be interpreted as meaningful. But let’s not get too excited. Every downtrend has its rallies.

* * *

Why does it seem necessary for cultural producers to go back in time in order to show reasonably civilised behaviour? (Though it’s certainly not a sufficient condition — see for example Ripper Street, or Rome.)

The argument that producers reflect the realities of the time they are portraying seems like only partial explanation. Culture does not merely reflect, it selectively reinforces. In the modern era, it is as much cause as effect.

Other reviewers of Howard’s End have felt obliged to comment unfavourably on the socioeconomic inequalities, which supposedly cast a moral blight on the otherwise attractive lifestyles of the cultured middle class. This is standard, knee-jerk stuff.

Conversely, then, we can hypothesise that the dominant ideology requires the suppression of qualities which could be seen as supportive of inequality, at least in representations of contemporary life. According to this logic, politeness (for example) is seen as bourgeois, and as something which should be discouraged in favour of open aggression. Representations of the past may be exempt from this requirement, because the ideology now includes the well-accepted tenet that, on balance, the past can be ignored — it is useful only in providing illustrations of how not to run things.

08 December 2017

number one voice

“Beautiful” here means: pure, free of distortion, an unalloyed pleasure to listen to. Like a perfectly tuned musical instrument. A strawberries-and-cream voice.

(Not the same as “most expressive voice”, an accolade which might well go to Maria Callas.)

There is an excellent case for Kathleen Battle; particularly when singing Mozart, which brings out her strengths.

Battle made a superb recording of Mozart arias with André Previn in the mid-eighties. You can listen to one of the tracks here.

01 December 2017

spellcheck #5

Here is another Latin-based expression that’s in danger of being murdered by misspelling: per se. The phrase is used to mean in itself or by itself, often in the context of a negative.

The spelling “per say” gets c. 600K Google hits, though most are articles pointing out the mistake.

The example I’ve just come across is from E E Holmes’s otherwise well-crafted Gateway ghost-comedy-thriller series.

From book 4 in the series, Whispers of the Walker (Kindle version).

RIGHT:

I don’t have a thing against magnolias per se, just the one in my garden. (Guardian)

The spelling “per say” gets c. 600K Google hits, though most are articles pointing out the mistake.

The example I’ve just come across is from E E Holmes’s otherwise well-crafted Gateway ghost-comedy-thriller series.

WRONG:

There’s no official probation, per say, in Durupinen law.

From book 4 in the series, Whispers of the Walker (Kindle version).

24 November 2017

languagecheck

Wikipedia defines OPEC as an intergovernmental organisation which attempts to coordinate the petroleum policies of member countries. In practice, most consider OPEC to be a cartel, trying to maximise profits by agreeing production quotas.

Is it helpful for a cartel to have a leader? Economics tries to answer this question using game theory, but it’s not clear how helpful that approach is. Conditions prevailing in the real world are typically too complex to be captured by current game-theory models. Simple psychology suggests the answer is: yes, having a leader makes it easier to coordinate behaviour.

Roughly speaking, OPEC countries’ petroleum represents about half of the global total, and Saudi Arabia controls about a quarter of that. By comparison, the next biggest members in terms of production, Iran and Iraq, each generate about a tenth of OPEC’s output.

Saudi Arabia has no formal leadership status. OPEC’s chief executive from 2007 to 2016 was Abdalla Salem el-Badri, a Libyan. Yet in practice Saudi Arabia seems to play a dominant role in OPEC’s decision-making. It is therefore sometimes said to be OPEC’s “de facto leader”.

de facto here means:

- actual or in practice, while not corresponding to the legal or formal framework

(More examples of usage at dictionary.com)

In a recent Reuters article, de facto appears to have got Chinese-whispered into defector:

* In the earlier article, Reuters spells the phrase “de-facto leader”. Hyphenating compound modifiers is usually desirable, as it helps to avoid ambiguity. When, as in this case, the modifier is a foreign phrase, a hyphen seems superfluous.

Is it helpful for a cartel to have a leader? Economics tries to answer this question using game theory, but it’s not clear how helpful that approach is. Conditions prevailing in the real world are typically too complex to be captured by current game-theory models. Simple psychology suggests the answer is: yes, having a leader makes it easier to coordinate behaviour.

Roughly speaking, OPEC countries’ petroleum represents about half of the global total, and Saudi Arabia controls about a quarter of that. By comparison, the next biggest members in terms of production, Iran and Iraq, each generate about a tenth of OPEC’s output.

Saudi Arabia has no formal leadership status. OPEC’s chief executive from 2007 to 2016 was Abdalla Salem el-Badri, a Libyan. Yet in practice Saudi Arabia seems to play a dominant role in OPEC’s decision-making. It is therefore sometimes said to be OPEC’s “de facto leader”.

de facto here means:

- actual or in practice, while not corresponding to the legal or formal framework

(More examples of usage at dictionary.com)

In a recent Reuters article, de facto appears to have got Chinese-whispered into defector:

OPEC’s defector leader is focused on reducing global oil stocksD’oh! Interestingly, six months earlier, Reuters was still getting it right.*

* In the earlier article, Reuters spells the phrase “de-facto leader”. Hyphenating compound modifiers is usually desirable, as it helps to avoid ambiguity. When, as in this case, the modifier is a foreign phrase, a hyphen seems superfluous.

17 November 2017

Plunging back into a dark age

Celia Green:

from The Decline and Fall of Science

The recent peak of civilisation, centred on Western Europe, from which we are in the process of declining, was the highest that the world has known. At its height, it encompassed scientific and philosophical ideas which had not previously been formulated. However, in doing so, it brought about its own downfall. In both science and philosophy it came too close to areas of thought which the human race wishes to avoid. Consequently, it became necessary to plunge back into an intellectual dark age, and this is a process which the human race has already brought to quite an advanced stage in the present century. [...]

In these circumstances, the European mind took refuge in a social and intellectual revolution. The social revolution was designed to make it impossible for individuals to think, or express inconvenient thoughts. It should be made impossible for anyone to have time to think unless he performed this function as a paid agent of society. Society, naturally, would know how to select in favour of those who thought in approved ways. While the social revolution has been fairly obvious, the intellectual revolution (or the abolition of dangerous thought) has attracted little attention. But the fact remains that in all operative fields of thought the human race has involved itself in positions from which, on their own terms, no advance is possible.

from The Decline and Fall of Science

10 November 2017

Universities: from free speech to closed shop

A difficulty with analysing the ideology underlying current culture is that much of it is covert. This makes it harder to criticise, which may be the intention.

Occasionally, someone gets more explicit. This may not be in the relevant person’s best interests but can be informative.

As an example of what is wrong with contemporary academia, consider the following assertions recently made by an Oxbridge academic in a newspaper article. (I have paraphrased to prevent identification, as I have no desire to generate negative attention for the person concerned. More deserving of disapproval are those who adopt similar attitudes, or are complicit in allowing such attitudes to become influential, but who take care not to reveal their own position in print.)

Now many may like the idea of fighting against right-wing, or other ideologically incorrect, ideas. The question arises, however: is campus a suitable place for this?

The purpose of universities is (or should be) to consider ideas by reference to whether they fit with the facts, or are helpful in understanding reality; not by whether they fit with some principle of morality or other belief system.

Note the writer’s assertion that there is no such thing as neutrality. The ostensible effect of this is to undermine the argument I just made against activism on campus. If neutrality is not possible, or its apparent presence is a deception, then one cannot complain about its absence. This may of course be the motive for making the assertion.

“We must agitate”, says the writer. In other words, it is not enough that certain viewpoints may only be discussed as positions to be rejected — we must make it unpleasant for anyone who tries to argue in favour of such viewpoints.

If you want to know why the principle of free speech is being eroded, in universities and elsewhere, part of the answer is clearly: because many ‘academics’ consider it irrelevant.

Occasionally, someone gets more explicit. This may not be in the relevant person’s best interests but can be informative.

As an example of what is wrong with contemporary academia, consider the following assertions recently made by an Oxbridge academic in a newspaper article. (I have paraphrased to prevent identification, as I have no desire to generate negative attention for the person concerned. More deserving of disapproval are those who adopt similar attitudes, or are complicit in allowing such attitudes to become influential, but who take care not to reveal their own position in print.)

Universities have political significance.

The election of Donald Trump and the rising dominance of the Right provides an incentive for increased efforts in activism.

Many have queried the white bias on campus which presents bourgeois reading lists under cover of “neutrality”.

The question “What should be done?” is on everyone’s minds.

We must scrutinise our teaching materials. There are excellent schemes which attack class bias in academia. It is our responsibility to implement them.

There is no such thing as an apolitical classroom. We must realise that not taking a stand, or presenting a guise of neutrality, is equal to complicity.

We must agitate and organise so that our students speak up, make the world a better place, and do not become complicit in its evils.

Now many may like the idea of fighting against right-wing, or other ideologically incorrect, ideas. The question arises, however: is campus a suitable place for this?

The purpose of universities is (or should be) to consider ideas by reference to whether they fit with the facts, or are helpful in understanding reality; not by whether they fit with some principle of morality or other belief system.

Note the writer’s assertion that there is no such thing as neutrality. The ostensible effect of this is to undermine the argument I just made against activism on campus. If neutrality is not possible, or its apparent presence is a deception, then one cannot complain about its absence. This may of course be the motive for making the assertion.

“We must agitate”, says the writer. In other words, it is not enough that certain viewpoints may only be discussed as positions to be rejected — we must make it unpleasant for anyone who tries to argue in favour of such viewpoints.

If you want to know why the principle of free speech is being eroded, in universities and elsewhere, part of the answer is clearly: because many ‘academics’ consider it irrelevant.

31 October 2017

500 years after Luther

Luther — in this, and other publications — noted that the ideals of the Church had become corrupted. Corruption had happened gradually, involving a succession of distortions, each of which by itself may have been regarded as convenient and acceptable.

The net effect was that key concepts, such as repentance, which originally meant one thing had come to mean something quite different.

Luther’s observations of corruption were on a local scale, but the deterioration in the Church’s standards was global. A huge number of functionaries were operating within a system that had abandoned the standards which made that system meaningful. Many of them must have been aware of deterioration, but thought it was not in their interests to draw attention to it.

Indocte et male faciunt sacerdotes ii, qui morituris penitentias canonicias in purgatorium reservant.

Ignorant and wicked are the doings of those priests who, in the case of the dying, reserve canonical penances for purgatory.

It did not take genius to write an uncompromising attack on the defects. It did, however, require honesty and courage.

Today there are parallel defects in the modern equivalent of the Church’s intellectual edifice: the universities. We need an analogous critique of deterioration. We need a return to earlier principles. Indeed, we may need something deserving of the term ‘revolution’.

20 October 2017

Revolution - III

Authorities are bewildered, heads of institutions try threats and concessions by turns, hoping the surge of subversion will collapse like previous ones. But none of this holds back that transfer of power and property which is the mark of revolution and which in the end establishes the Idea ...

When people feel that accretions and complications have buried the original purpose of an institution, when all arguments for reform have been heard and have failed, the most thoughtful and active decide that they want to be “cured of civilization”.

... The priest, instead of being a teacher, was ignorant; the monk, instead of helping to save the world by his piety, was an idle profiteer; the bishop, instead of supervising the care of souls in his diocese was a politician and businessman ... When people accept futility and the absurd as normal, the culture is decadent.

Jacques Barzun, From Dawn to Decadence

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)